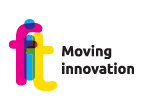

More movement or more meaningful access? Rethinking mobility for more equitable cities

Mobility or the ability to move freely across a city should not be solely about expanding infrastructure but also about designing systems that allow everyone to reach their destinations comfortably and conveniently, while considering individual needs and limitations.

Around the world, cities are in a rush to expand transportation networks, but this effort often overlooks deeper, systemic challenges: economic segregation, social isolation, and unequal access to essential services. Even the most advanced mobility systems can fail to address these root causes if they’re built only to move people faster or farther. Some cities are now reframing the problem entirely—rethinking whether the goal is more movement, or more meaningful access.

How freely can people choose not to move?

For urban policy-makers and mobility professionals, this means rethinking the very concept of mobility—not just as movement, but as a tool for access and opportunity. The question is shifting: no longer “How do we move people faster?”, but “How can we bring services closer, so that people don’t need to travel as much?”

This reframing aligns with the needs of those who have limited mobility or fewer opportunities to travel, as well as with climate adaptation goals and citizens’ growing demand for a better quality of life.

Interventions need not come with prohibitive costs. Tactical urbanism, pilot projects, and data-driven tools allow for rapid testing and adaptation, an agile approach that gives cities the confidence to iterate and scale successful models.

Paris continues to invest in the “15-minute city” model, ensuring that essential services, workplaces, and recreational spaces are within easy reach of every resident. The idea is to reduce the need for long commutes and empower people to live more locally, sustainably, and meaningfully.

Yet infrastructure alone isn’t enough. Cities like Helsinki and Stockholm are showing how digital multimodality—the ability to access services like healthcare and education remotely—can complement physical infrastructure, especially in reducing unnecessary trips for residents with limited mobility. This is not about replacing transport, but expanding access options, especially in underserved or remote areas. Of course, any shift toward digital access must also consider the digital divide, ensuring that solutions don’t reinforce existing inequalities.

Active Travel (AT)—especially walking and cycling—plays a central role in building equitable and efficient urban transport networks. These modes of transport are accessible, affordable, and environmentally sustainable. Beyond health and congestion benefits, AT fosters community cohesion by enabling more local relationships and a stronger sense of belonging.

Yet, despite its advantages, urban planning has historically prioritized private vehicles, resulting in underinvestment in walking and cycling infrastructure. This imbalance has prevented cities from creating truly multimodal systems that encourage sustainable, inclusive travel.

Tokyo, one of the most functional cities in the world, is also one of the most pedestrian-friendly – and it’s not a coincidence. Car use is driven by regulation. The city imposes high ownership costs and strict requirements, including the obligation to secure a “garage certificate” (shako shomeisho), which proves that the buyer has a private parking space within two kilometers of their residence. On-street overnight parking is prohibited, and parking fees are among the highest in the world, often exceeding €8 per hour. These measures successfully discourage unnecessary vehicle ownership and promote the use of Tokyo’s world-class public transportation system.

Traffic-calming strategies also play a significant role in making mobility more inclusive and safer. Lowering speed limits from 50 km/h to 30 km/h is often met with resistance, as drivers worry about longer journey times. However, data shows that the difference in travel time is usually less than a minute, while the impact on safety as well as experience of urban life is dramatic.

In New York, congestion pricing reduced traffic by 7.5%—the equivalent of 43,000 fewer cars per day. Since January 2024, Bologna has become Italy’s first major city to widely adopt a 30 km/h speed limit across most of its urban streets. A year later, data clearly demonstrate tangible benefits from the speed reduction: daily traffic has dropped by over 11,000 vehicles; bicycle usage has increased by 10%; bike-sharing services have surged dramatically (+69%); car-sharing use has significantly grown (+44%); and the metropolitan railway service (Sfm) has recorded a 31% increase in passengers. Concurrently, nitrogen dioxide emissions—directly linked to vehicle traffic—have decreased by 29%, supported by concrete infrastructural improvements including new pedestrian squares, expanded cycling paths, and safer pedestrian crossings.

We must therefore ask: who is being excluded by our current mobility systems, and why? Rethinking mobility also means redefining success—not in terms of speed or traffic volume, but in terms of equity and access.

In Edinburgh, urban planning is shifting perspective, rooted in a deeper reflection on who public spaces are truly designed for—with a specific focus on safety. In this context, transport plays a crucial role: late-night travel remains a challenge, due to infrequent bus services and expensive taxis. That’s why the city is working to redesign pavements, lighting, resting areas, and accessibility with the goal of making public spaces safer, more livable, and accessible at all times of day.

These examples invite reflection and serve as a reminder that there is no single solution, but a set of strategies—infrastructural, digital, regulatory, and social—to transform and support mobility as a driver of connection, not a privilege for the few.